There comes a point in time where every story, no matter how emotional, gets sadly repetitive.

In the case of aggression against Coptic Christians, that point was reached a long time ago.

On February 13, 2015, 21 Coptic Christian men were killed in Libya. They were working there to support their families in Egypt. They were abducted by armed Libyans in recent weeks, apparently due to their faith, and were killed by those militants by beheading on a beach. According to the video that shows the beheading, these men were killed as a retaliation to the “hostile Egyptian church”.

These details show a very serious political, social and ideological motivation behind these gruesome killings. They are an important part of a horrific picture being painted in the Middle East today by ISIS militants. And as the horror of ISIS grows, more questions are raised about who they are, where they operate, and what steps to take to stop them.

I present you with my dissection of the Egyptian airstrikes against ISIS targets in Libya, and what they could mean for the future of Egypt’s war with ISIS.

The Big Picture (from a Coptic perspective)

ISIS militants have seemingly taken an all-out, “gloves are off” approach towards advancing their goals. Since they rose to prominence in 2014, rumours of the atrocities ISIS were committing in Iraq and Syria had never really hit home for North Americans. It was only well-known to those who closely followed the situation (perhaps due to their ethnic origin from Iraq and Syria) or those seeking to influence some sort of policy change on the matter (FOX News has been active on that front, but perhaps for non-altruistic reasons). Perhaps, on some level, we did not want to know what it was they were doing.

But the fact of the matter is that ISIS has long made it known to the world their intentions. In 2014, a widely known fact was that ISIS militants in Iraq were marking homes of Christians by the Arabic letter “noon“, to denote that the owners of this house are Nazarenes (a derogatory term used by Islamists to describe Christians). The purpose of these markings was simple: when the time came to cleanse the country of “non-believers”, Christian homes could be more easily targeted.

The latest killing of Coptic Christians, which ISIS has officially declared war with and has called on all its followers to “kill all Copts in the world, wherever they may be”, is simply the escalation of ISIS’ ethnic cleansing efforts.

For Coptic Christians, it’s the realization of a very real fear that they have held for some time: there is a storm coming, and it is already at their shores in Egypt. In the eyes of most Copts, all that stands between their annihilation and survival is an Egyptian military that is seemingly becoming a lone Arab fortress in the Middle East.

Obama’s second doubts

The traditional power balance in global politics is currently undergoing a major re-configuration. The United States, normally seen as a major policing force in the world, is reluctant to jump into the madness of Iraq after a long and drawn-out war. For the Obama administration, a re-engagement in Iraq would be a difficult pill to swallow. By re-engaging in Iraq, there is the inadvertent admission of a mistake in puling out initially. Furthermore, there is the uncertainty of the length of a war in Iraq: would they be able to “finish the job” in 2 years? 4 years? 10 years? Who knows.

But even if there was no hesitancy, the geo-political scenario does not present an appeal for engagement. The United States would need the assistance of various geographic allies in the region in order to be able to pull this off effectively. Under Obama, many key players in the Middle East have distanced themselves from the United States, and has caused many traditional allies in the Middle East to view the United States as an ISIS supporter (for example, Egypt’s administration sees the US condemnation of Egyptian airstrikes on Libya as an endorsement of ISIS atrocities).

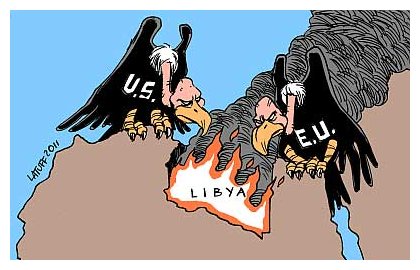

On the face of it all, it does seem that the United States is taking an opposing stance to Egypt’s so-called “war on terror”. But could the US stance just be the result of a new approach to the Libyan airstrikes of 2011?

Lessons learned from Libya

In March 2011, NATO members led a military intervention in Libya in order to implement UN Security Council Resolution 1973 (adopted March 17 2011). This resolution provided the legal basis to establish a no-fly zone in Libya in order to allow for all the means necessary to protect Libyan citizens short of foreign occupation. This was in response to concerns that then-leader Muammar Gaddafi would use force against his own people, who were rebelling against him in the wake of the Arab Spring.

Although it seemed like a protective measure for the Libyan people, the measure ended up being the death spell for Gaddafi and his regime. By October of that year, Gaddafi was killed by the rebel forces he sought to overcome, and the country descended into an ambiguous state of civil war where no one government has been able to hold the country together.

It was in that chaos that the rebel groups found fertile ground to grow. Among those groups, of course, were ISIS (Islamic State in Iraq and Syria) – they had gained control over the whole town of Derna by November 2014.

For the NATO coalition that led the airstrikes against Gaddafi, this started to look like a multi-headed beast, where cutting off one head leads to another. It may have also been part of a pattern – why is it that, in every part of the world where airstrikes and military intervention topples one regime, another one way worse comes up after?

Perhaps the time had come for Libya to be part of a new experiment – the implementation of some form of government through diplomatic means, as opposed to “hot-wiring” a new government into existence.

The right to self-defence in International Law

In the hours that came after the video was released, and the captives were confirmed killed, Egypt’s El-Sisi took to the Egyptian airwaves to “reserve” Egypt’s right to retaliation. This right, based apparently in self-defence, can be argued as a fundamental concept preserved in international law. Under article 51 of the UN Charter, member states have an inherent right to self defence “if an armed attack occurs against a member of the United Nations”. However, there is an important caveat that limits this right, stated in the same article as follows:

“[…] until the Security Council has taken the measures necessary to maintain international peace and security. Measures taken by members in exercise of this right of self-defence shall be immediately reported to the Security Council and shall not in any way affect the authority and responsibility of the Security Council under the present Charter to take at any time such action as it deems necessary in order to maintain or restore international peace and security”

You might be wondering why the UN Security Council has such an overwhelming monopoly on the right to self-defence. This is primarily due to the prohibition of the use of force established in Article 2(4) of the UN Charter, which prohibits the threat or use of force. This cuts to the core of the existence of the United Nations – a political-legal body established to prevent and outlaw wars, and to encourage a diplomatic resolution to any conflicts among its member states. It’s because of that prohibition that the UN Security Council holds an overwhelming veto on the use of force in international affairs.

However, keep in mind that the right to self-defence is not as simple as it seems. Under international law, there has to be “necessity” and “proportionality” in the exercise of self defence. This means that your actions in self-defence have to adequately defend your threatened interests (e.g. security, border integrity, etc) and must be proportionate to the danger (e.g. addressing armed resistance with the use of force).

Many have hailed Egypt’s response to the murder of its 21 citizens as many things. Some saw it as a courageous and exemplary defense of the value of Egyptian citizenship, some saw it as a necessary push towards destabilizing ISIS, and some saw it as a necessary push to re-stabilize a badly divided Libya. Although the political motivations are not immediately clear, Egypt’s exercise of the right to self-defence is arguably within the confines of what is permitted in international law.

This presents an interesting contradiction in El Sisi’s presidency so far. When it comes to taking action in the formal international arena, he looks to and relies on the law to proceed legally. Yet, when it comes to the implementation of his own international obligations within his own borders, he seems to have no problems ignoring those obligations (for example, inter alia, the draconian protest law passed in 2014).

Has Egypt violated the Geneva Conventions?

Assuming that Egypt has exercised its right to self-defence legally, one must then turn to analyze the impact of its decision. This is an important step to determine if Egypt has met other international obligations related to human rights, such as its obligations under the Geneva Conventions (which prohibit the indiscriminate killing of civilians during armed conflict, among other things).

In the days that followed the Egyptian airstrikes on Derna, Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch condemned the airstrikes as potential war crimes, claiming that seven civilians were killed by Egyptian jets. In response, the Egyptian army has vehemently denied these allegations, saying that they are based on false information. In addition, the Egyptian army has re-iterated that it carried out the airstrikes with precision, and that it had compiled extensive intelligence about the region prior to the video’s release.

These two very different sides of the story make it difficult to say with any certainty whether there was indeed a violation of Egypt’s Geneva Convention obligations. As of the time writing this, there has been no independent investigation on the ground conducted on the alleged deaths – Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch have both based their reports on eyewitness testimonies.

As of right now, one cannot know for certain if Egypt exercised its right to self-defence in a legal way. This may never be known, as Libya’s state of chaos makes it difficult to confirm anything on the ground.

What comes next?

Egypt’s response to this measure should be calculated and objective. Although there have already been airstrikes conducted against ISIS targets in Libya, there should be careful consideration as to whether further airstrikes will cause further aggression to Copts in Libya, or whether it may have an adverse effect on other Egyptians in the region. Whatever the political motivations for these airstrikes are, if they entail further acts of aggression against Egyptian citizens, then every effort should be made to prevent unnecessary aggression and to keep civilians out of any acts of armed aggression against ISIS. For as much as El Sisi might have some footing in international law to strike against enemies, he also has an international obligation to protect his citizens, whether he’s shooting at them directly, or allowing his citizens to fall in the hands of their murderers.